Book Description

India | International

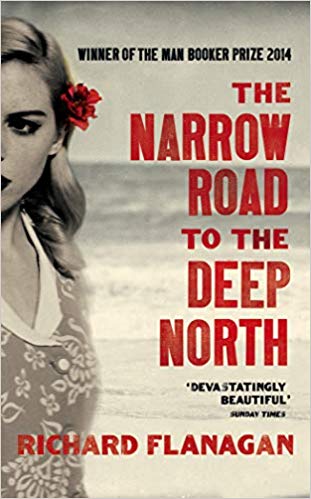

The Narrow Road to the Deep North is the sixth novel by Richard Flanagan.

It takes its title from 17th-century haiku poet Matsuo Bashō‘s famous haibun Oku no Hosomichi, best known in English as The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

It won the 2014 Man Booker Prize.

Book Summary

The book centres upon the experiences of surgeon Dorrigo Evans in a Japanese POW camp on the now infamous Thailand-Burma railway.

‘elegantly wrought, measured and without an ounce of melodrama… nothing short of a masterpiece.’

The Financial Times

The Man Booker prize judges described the book as ‘a harrowing account of the cost of war to all who are caught up in it’. Questioning the meaning of heroism, the book explores what motivates acts of extreme cruelty and shows that perpetrators may be as much victims as those they abuse. Flanagan’s father, who died the day he finished The Narrow Road to the Deep North, was a survivor of the Burma Death Railway.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North Quotes

Lets start with my favourite quote. Read my article on ‘A Happy Man Has No Past.’

A HAPPY MAN has no past, while an unhappy man has nothing else.

And in the deepest recesses of his being, Dorrigo Evans understood that all his life had been a journeying to this point when he had for a moment flown into the sun and would now be journeying away from it forever after. Nothing would ever be as real to him. Life never had such meaning again.

It was as if life could be shown but never explained, and words—all the words that did not say things directly—were for him the most truthful.

He loved his family. But he was not proud of them. Their principal achievement was survival. It would take him a lifetime to appreciate what an achievement that was.

In the years that for most his age were termed declining he was once more ascending into the light.

He believed books had an aura that protected him, that without one beside him he would die. He happily slept without women. He never slept without a book.

He found in the time he was able to spend with Tom—by phone once a month and what became after a time an annual visit to Sydney in midwinter, and then, as his reputation grew and he travelled to Sydney more frequently—that special closeness that siblings sometimes have. It was an ease of company that allows for most things to be unsaid, for awkwardness and error to be entirely unimportant, and for that strange sense of a mysterious shared soul to be expressed through the most trivial of small talk.

A good book, he had concluded, leaves you wanting to reread the book. A great book compels you to reread your own soul.

And Amy Mulvaney wanted a thousand lives, and not one of them did she want to be like the one she had.

It’s like this, Mr Kimura, said Sato. There is a pattern and structure to all things. Only we can’t see it. Our job is to discover that pattern and structure and work within it, as part of it.

And this sense, this feeling of communion, would at moments overwhelm him. At such times he had the sensation that there was only one book in the universe, and that all books were simply portals into this greater ongoing work—an inexhaustible, beautiful world that was not imaginary but the world as it truly was, a book without beginning or end.

Memory is the true justice, sir. Or the creator of new horrors. Memory’s only like justice, Bonox, because it is another wrong idea that makes people feel right.

Horror can be contained within a book, given form and meaning. But in life horror has no more form than it does meaning. Horror just is. And while it reigns, it is as if there is nothing in the universe that it is not.

Read More Like This

- The North Water by Ian McGuire – Book Review

- The Supernova Era by Cixin Liu – Book Review

- A Happy Man Has No Past

Recent Articles