A postcard on the orthodoxy on originality that plagues today’s society.

Today’s society puts creativity and innovation on a pedestal with imitation in any form frowned upon.

Society’s demand for originality affects most creators.

The demand for originality and an increasingly ‘winner-takes-it-all’ marketplace creates a race to be the ‘first’ or ‘original’ in every sphere of human activity.

But is anyone, ever, truly original?

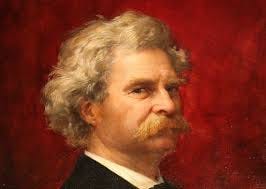

Mark Twain views plagiarism as the kernel, the soul of all human utterances.

Oh, dear me, how unspeakably funny and owlishly idiotic and grotesque was that ‘plagiarism’ farce! As if there was much of anything in any human utterance, oral or written, except plagiarism!

The kernel, the soul — let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances — is plagiarism.

For substantially all ideas are second-hand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources, and daily used by the garnerer with a pride and satisfaction born of the superstition that he originated them; whereas there is not a rag of originality about them anywhere except the little discoloration they get from his mental and moral calibre and his temperament, and which is revealed in characteristics of phrasing.

When a great orator makes a great speech you are listening to ten centuries and ten thousand men — but we call it his speech, and really some exceedingly small portion of it is his. But not enough to signify. It is merely a Waterloo. It is Wellington’s battle, in some degree, and we call it his; but there are others that contributed.

It takes a thousand men to invent a telegraph, or a steam engine, or a phonograph, or a telephone or any other important thing — and the last man gets the credit and we forget the others. He added his little mite — that is all he did.

These object lessons should teach us that ninety-nine parts of all things that proceed from the intellect are plagiarisms, pure and simple; and the lesson ought to make us modest.

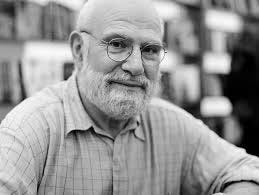

Oliver Sacks adds:

All of us, to some extent, borrow from others, from the culture around us.

Ideas are in the air, and we may appropriate, often without realizing, the phrases and language of the times.

We borrow language itself; we did not invent it. We found it, we grew up into it, though we may use it, interpret it, in very individual ways.

What is at issue is not the fact of “borrowing” or “imitating,” of being “derivative,” being “influenced,” but what one does with what is borrowed or imitated or derived; how deeply one assimilates it, takes it into oneself, compounds it with one’s own experiences and thoughts and feelings, places it in relation to oneself, and expresses it in a new way, one’s own.

Here’s Steve Jobs, the man we consider to be the creative genius of our times.

Creativity is just connecting things.

When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things.

And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people.

Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity.

A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem.

The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

Salvador Dalí put it succinctly:

Those who do not want to imitate anything, produce nothing.

Read More Like This

Recent Articles